Born during the first year of the Meiji era, Natsume Soseki (1867-1916) and Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) became influential writers, Soseki as a novelist and Shiki as a poet, for the new age. They became friends in college and remained close until Shiki's early death.

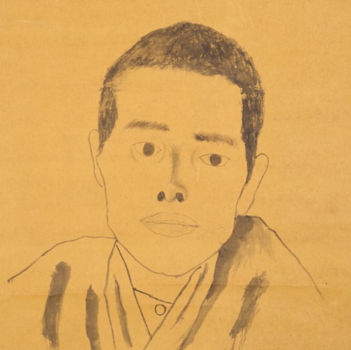

Shiki's Painting

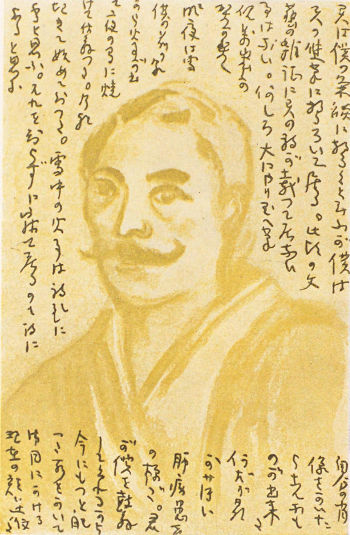

Natsume Soseki

I have one painting by Shiki. This memorial to my late friend had been stored in a pouch for some time. As the years passed, I often forgot the whereabouts of the pouch. Recently, I suddenly remembered. It had probably been misplaced during some move. I soon took the painting to a picture hanger to be framed for hanging. When I pulled out the tanned-paper bag to dust and inspect the painting, it was still damp and folded in four. Several letters from Shiki came out unexpectedly along with the painting. Among them were the final letters Shiki wrote to me. I selected a short one of some unknown date. A few paintings were sandwiched in between. I had three of them mounted together.

One picture depicted a China aster in a rose vase. The design was quite simple. When I looked at the note added on the side, "This looks withered. I think it's pretty bad because I'm ill. If you think I'm lying, I drew it while resting on my elbows." I probably didn't think it was any good either. When Shiki painted this picture, I wasn't in Tokyo. He added a poem to the painting about arranging the China aster and my returning home to Hinokuni, and sent it to me in Kumamoto.

When I hung the painting on the wall and looked at it, it had an air of loneliness. Only three colors were used for the flowers, the stems, and the glass vase. One flower had only two buds. I counted the leaves. There were nine. No matter how I stared at it, I was struck by the coldness of the surrounding whiteness and the indigo silk of the frame.

It seems that Shiki spared no effort to draw this simple flower. He took at least five or six hours to painstakingly paint just three flowers. Not only did this meticulous work require determination as a task demanding patience while ill, it was a clear contradiction to his easy-going nature when he wrote haiku or a song. As a man inexperienced in conveying his thoughts through images, he heard from the artist [Nakamura] Fusetsu and others about the need to draw from nature in contemporary paintings. As he intended to apply this idea to each blade of grass and each flower, did he forget to apply the same method that already enlightened his haiku to this field, or, perhaps, he lacked the ability to apply this technique.

Shiki's paintings typified by the China aster are clumsy and earnest. I could not keep from smiling at the thought of him summoning his genius to write, and at the same time the pigments were soaking into the palette and hardening instantly making the motion of the tip sluggish. When [Takahama] Kyoshi came to see this copy, he said that Masaoka's picture was good. At that time, I replied that I thought so much time and effort had to be expended to bring out that much distinctive simplistic mediocrity; and somehow when Masaoka's head and hand seemed forced into unneeded movements, the clumsiness he could not hide spilled out. It's impossible to be unpleasantness to and make flippant remarks about one who was so honest and straightforward to a fault. If there is a positive aspect, Shiki's painting possessed sweetness in spite of its useless simplistic honesty. In the momentary action of a line or a stroke, however, if one does not have the gift for making an argument on the spot for a feature that should settle the matter once and for all, the short-cuts of inevitable omissions are discarded, and precise Tomatsu-ism is methodically executed, then the word clumsy is difficult to escape.

As a human being and a man of letters, Shiki's biggest flaw was his clumsiness. In the months and days over the many years we were friends, I never tried to seize the opportunity to laugh at that clumsiness and never grew fond of it. Today, nearly ten years since his death, this clumsiness is revealed in this China aster he painted especially for me. This conclusion caused me to burst out laughing. Needless to say, I admired and held considerable interest in this painting. That single image was loneliness indeed. If possible, I wanted to make a slightly more spectacular show of this clumsiness in Shiki and make amends for that loneliness.

Note: The flowers in the background, although not the ones in this essay, were drawn by Masaoka Shiki. Retrieved April 17, 2016 from the National Diet Library Digital Collections.

Soseki's self-portrait is from The Complete Works of Natsume Soseki [漱石全集], Vol. 16. Retrieved June 30, 2016 from the National Diet Library Digital Collections.

Shiki's self-portrait is from Shiki Jiji Gashi Shouzou [子規居士自画肖像]. Retrieved April 17, 2016 from the National Diet Library Digital Collections.